The ever-active parks department of the Municipality of Arnhem really outdid itself this year: around the trees on the median of the Bakenbergseweg in Arnhem, a ribbon of crocuses in two colors bloomed around this spring. As creative as it was, it simultaneously confirmed that coloring outside the lines is a human intervention in nature—an act that channels the creative potential or innate inventiveness of nature. This paradox also characterized exhibitions in the Netherlands from the late 1960s onward that focused on art and nature.

One such example was Inside and Outside the Frame: Environments and Situations by Young Dutch Artists (Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 1970), a follow-up to the much better-known international exhibition Op Losse Schroeven (Square Pegs in Round Holes) held a year earlier in the same museum. Inside and Outside the Frame felt like a kind of addendum, featuring six Dutch artists. The term “micro-emotive,” introduced by Italian artist Piero Gilardi during the preparation of Op Losse Schroeven and later adopted by artists like Ger van Elk, found clearer expression in this context.

The tension between art and nature remained central to the following event and exhibition, Sonsbeek buiten de perken [Sonsbeek off the beaten track], where American artist Fred Sandback stayed neatly within bounds with his patch of salvias, while other artists moved tons of sand or chose the opposite extreme: a modest and studious engagement with something like a pasture management plan. In the twelfth essay of the book I’m currently working on, such examples are explored. Art historically, they can be classified under terms like land art, earth art, process art, arte povera, and Spurensicherung. Micro-emotive art is a less common term, often absorbed by its bigger sibling, arte povera.

The Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth (1972) report was then already on the horizon—an apt moment to give more attention to the relationship between art and nature. Still, the art world wasn’t exactly ahead of the curve, with the exception of Gijs van Tuyl, then a young curator at the Stedelijk Museum and the force behind Inside and Outside the Frame, and Wim Beeren, who curated the two other mentioned exhibitions. Van Tuyl kept the subject in mind and years later managed to get the Venice Biennale interested, making it the overarching theme of the 1978 edition. Van Tuyl and Gerhard von Graevenitz curated the Dutch contribution, which led to the traveling exhibition To do with Nature / Mit Natur zu Tun a year later.

Based on these exhibitions, micro-emotive art seemed to have won out in the Netherlands over the large-scale land art—although that would reemerge many years later. In one of the postscripts of my book, titled Ecologica, I revisit the subject by taking a look at the history of ecological research and activism in the Netherlands. It’s an early history that is virtually unknown to the general public but was hard to ignore in the 1960s, or even as early as the late 1940s. If biologists, plant disease experts, and ecologists themselves didn’t bring attention to it, the Provo movement certainly did in the mid-1960s.

C.J. Briejèr, director of the Plant Protection Service in Wageningen, already published in 1949 “Are We on the Right Track?”—an article warning about the negative consequences of monocultures and economies of scale. He continued sounding the alarm throughout the 1950s, the period in which the biologist herman de vries worked at Briejèr’s service and developed his ‘method’, crucial for the rest of his artistic career, there. In 1956, Briejèr warned about insect resistance to pesticides, and published in 1967 Silver Veils and Hidden Dangers: Chemical Preparations that Threaten Life, a well-known book also read by Provo member Roel van Duyn at the time.

With the upcoming exhibition of herman de vries at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, this is a good moment to reflect on this fascinating history. De vries as the only artist in the Netherlands who has stood knee-deep in the fertile clay of art, nature, and science of that era—and has never wanted to pull his boots out.

See also: Cees de Boer and Rob de Windt, ‘herman de vries, random objectivication v67-36c: Ecology as Context of a Systematic Art Work’, The Rijksmuseum Bulletin, vol. 72, no. 4 (2024), p. 317-343.

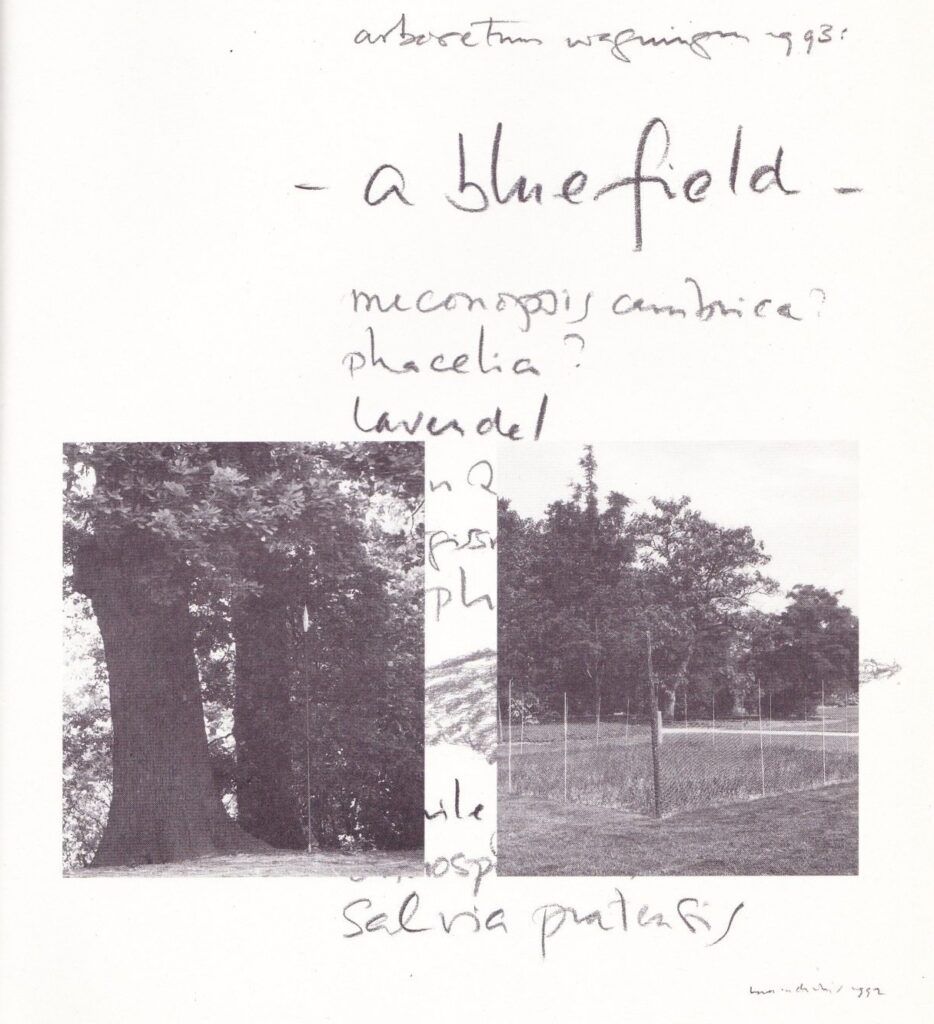

About the image:

‘in musée des beaux arts, musée des beaux arbres herman de vries presents two test fields cut into the lawns: a field with 32 wheat varieties and a field with oil flax (“the blue field”). wheat originated through a cultivation process that spanned thousands of years.

in “w h e a t” de vries shows the transformation from nature to culture. “f l a x”, also an ancient cultivated crop, is, when in bloom, of an enchanting blue — “the blue field”. a small trance according to herman de vries.

a third work is “speer neben alte eiche”. it is an ode to the pedunculate oak in belmonte arboretum. here, de vries lets us freely find meaning.’

(from: beelden op de berg 6, Belmonte Arboretum Wageningen, 1993)