Karesansui (Zen garden), installation with works by Shinkichi Tajiri and Ferdi in the exhibition The Restless Wanderer, Bonnefantenmuseum Maastricht (2 December 2023–12 May 2024)

Photo: Marga van Mechelen

It is not uncommon, after national elections, for commentators to lament the lack of attention paid to certain issues during the campaign. This time, it was climate change—but also sexual violence and femicide. This was the reason why the television program Buitenhof invited well-known court reporter Saskia Belleman, one of the initiators of a manifesto against femicide and domestic violence—and Femke Halsema, the mayor of Amsterdam, the city where, only a few months earlier, seventeen-year-old Lisa was murdered on her way home.

Although crime statistics often paint a less dramatic picture than public perception would suggest, femicide, it appears, is not declining. Belleman and Halsema came with this message on Sunday 3 November, along with the observation that the Netherlands—contrary to its own self-congratulatory image—has “a flawed history of emancipation.” Halsema further noted that attitudes toward sexuality have been changing in recent years, and “not necessarily for the better.” The domination and subjugation of women, she warned, is becoming more socially acceptable—something to be deeply concerned about. Again, we see a striking discrepancy between image and reality: the belief that “the Netherlands has always done so well” versus the facts. As Halsema pointed out, it was only in the mid-1970s that marital rape was made a criminal offense in the Netherlands.

While writing the essays for my forthcoming book on the art of the 1960s in the Netherlands, two questions lingered constantly above my screen: How did women’s emancipation fare within the particular ‘bubble’ that is my focus—namely, the visual arts in the Netherlands? And what, in that era, did “sexual liberation” actually mean? From my background as an art historian and semiotician, I take the facts seriously, but also the perception. The fact that the two are not always consistent with each other interests me less than the two pieces of signification and knowledge production themselves and their dialectic.

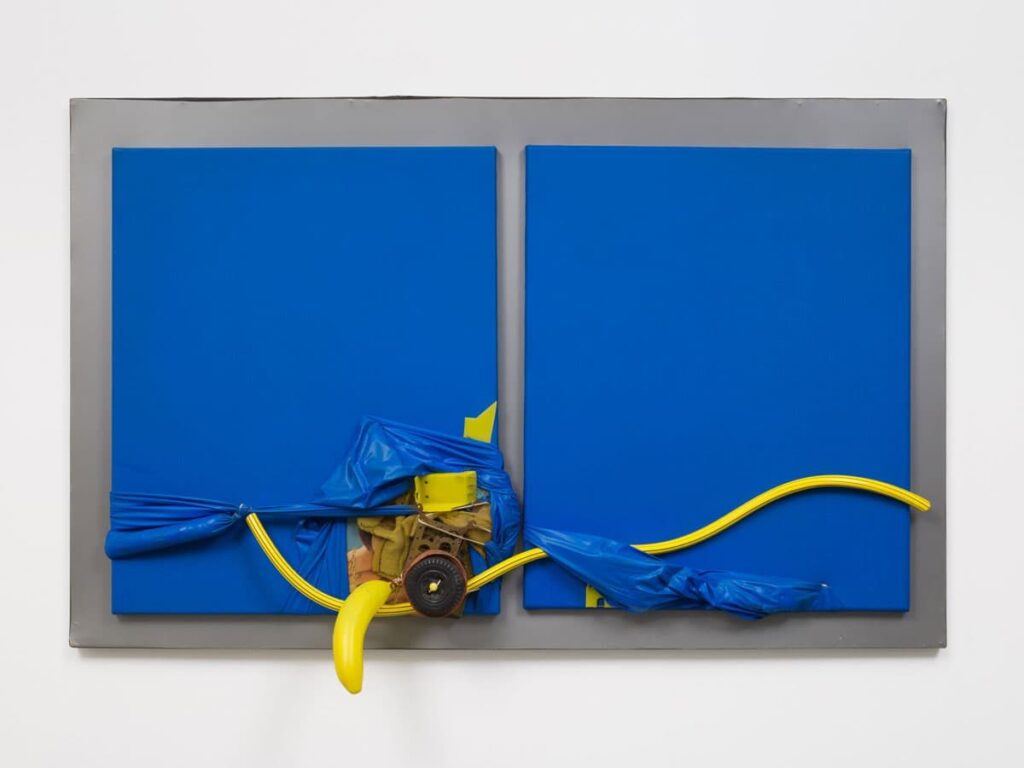

Miguel-Ángel Cárdenas, Blue lovers (1965), Panel, PVC, objects, 72.1 x 115.3 x 13.3 cm

Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

To give a simple example: the overly rosy image of sexual freedom in the Netherlands had a significant impact on the influx of homosexual (and activist) artists during the 1960s and 1970s—and consequently, on the art sector itself, to this day. When asked about their view of the Netherlands and their personal experience, ‘migrant art workers’ typically offered a very positive account. That perception has not changed much since. Most of them remained in the country, though economic reasons played a role as well.

In several essays, I refer to certain ‘facts’. Hitweek, for instance, functioned as a kind of proto–social media platform, long before the term existed— it offered its young readers plenty of opportunity to contribute to the magazine, also in matters of sexuality. Or the Wet Dream Film Festival (1970 and 1971), which was groundbreaking as the world’s first film festival devoted to pornographic, erotic, and underground cinema. It inspired similar festivals in San Francisco and New York shortly thereafter. Wet Dream was more than a film festival—it was a performance of sexual freedom as well. Within the confines of the club—membership being an official requirement—sexual interaction among participants was both real and theatricalized, framed in time and place as a kind of living showcase of liberation – referred to as a bacchanal.

Both representation and lived experience emerge vividly from the sources I consulted, mostly written by women, which was exceptional compared to other areas of art. It is clear, however, that with the hindsight of today, participants’ memories may have evolved.

In the realm of visual art in the more restricted sense, Sweden preceded the Netherlands. In 1968 and 1969, the first international exhibitions of erotic art were held there featuring two Dutch participants, Ferdi and Shinkichi Tajiri. However, the Hague Gallery OREZ, incidentally, had hosted earlier in the 1960s a couple of smaller exhibitions under the title Facets of Contemporary Eroticism with a prominent place for Yayoi Kusama (Miguel-Ángel Cárdenas exhibited here also; see illustration). Such a prominent place for a female artist in a mixed exhibition was exceptional in those years, and even when a female artist was exhibited in a leading gallery or museum, it was usually foreign women. Although many Dutch women artists in the 1960s built successful careers, receiving major commissions and invitations to international textile exhibitions for example, it was still rare for a woman to exhibit alongside her male peers.

There was, in the 1960s, still a long road ahead. That road began just before the decade’s end with the founding of Man Vrouw Maatschappij followed by Dolle Mina, and for women artists it gained real momentum only with the establishment of the Stichting Vrouwen en Beeldende Kunst (Foundation for Women and the Visual Arts, SVBK) in 1977, as well as the appointments of several female museum directors—Carry van Lakerveld in 1974, Josien de Bruyn Kops in 1976, and Liesbeth Brandt Corstius in 1982.

In the decades that followed, the optimistic image of a fully emancipated Netherlands was given time to mature. It was only during the second decade of this century, that I began to notice the change Halsema is referring to.

to be continued