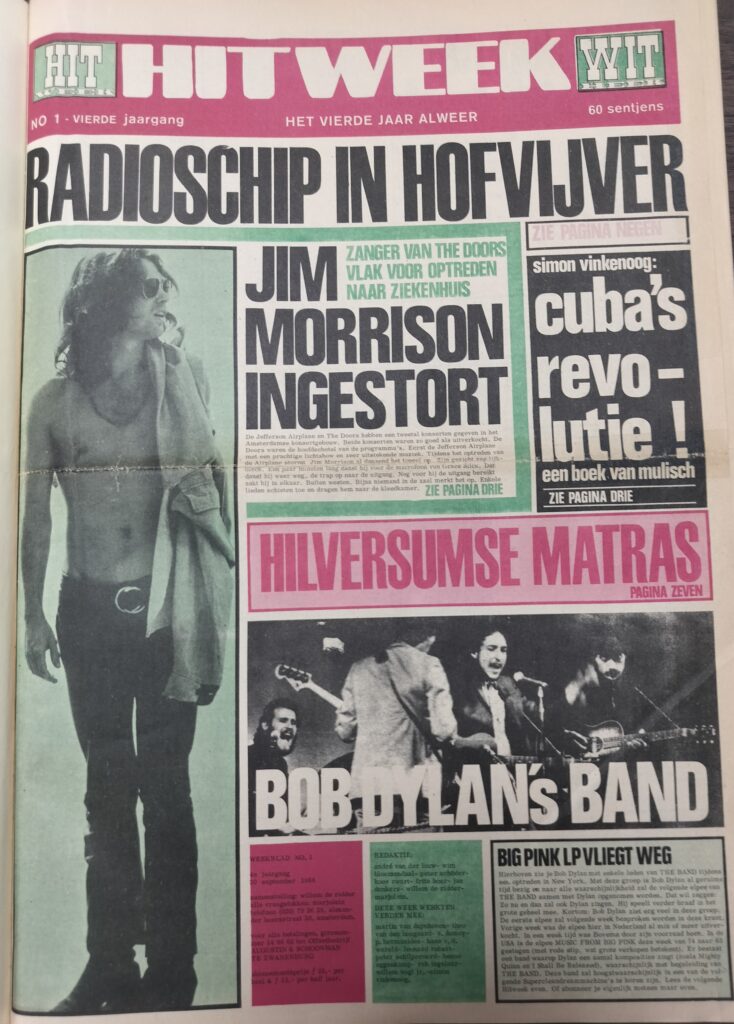

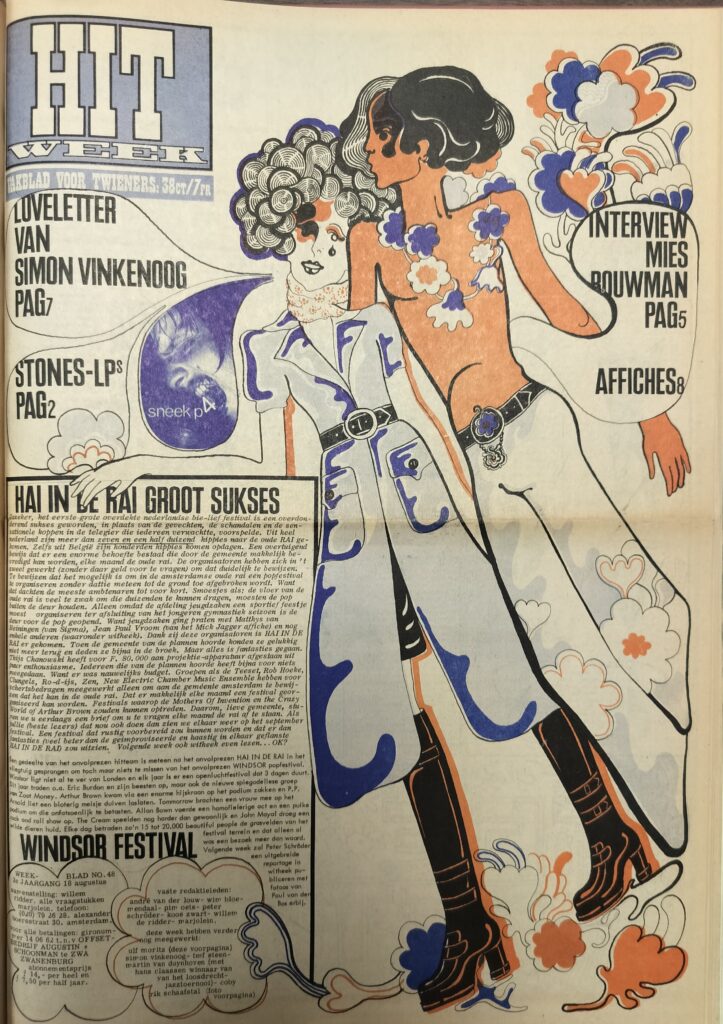

The word ‘Hitweek’, ‘the trade magazine’ for ‘twieners’, the name editor Willem de Ridder came up with, still has a magical ring to it. A weekly magazine, or should we call it a newspaper given its format, which was on sale throughout the Netherlands for thirty cents (“drie dubbeltjes”). Magical because it sums up everything that the image of the sixties stands for. First and foremost, the new pop music, the main ingredient of the magazine, which in the sentimental days before Christmas and New Year’s Eve can be heard even more than usual on the radio, secondly fashion, but also literature, and the manifestations of counterculture, which, coinciding with the founding of the magazine, took on a more mass form then and received a lot of media attention. Think of Provo, which had only been around for four months at the time. In my forthcoming book about the visual arts of the 1960s (and beyond), Hitweek could not be left out, especially Willem de Ridder (1922-2022), lent me his glasses, in exchange for which he is frequently mentioned in the book; he should have known! In a previous blog, I briefly mentioned Hitweek as a DIY magazine and an early form of social media. But is that really the case?

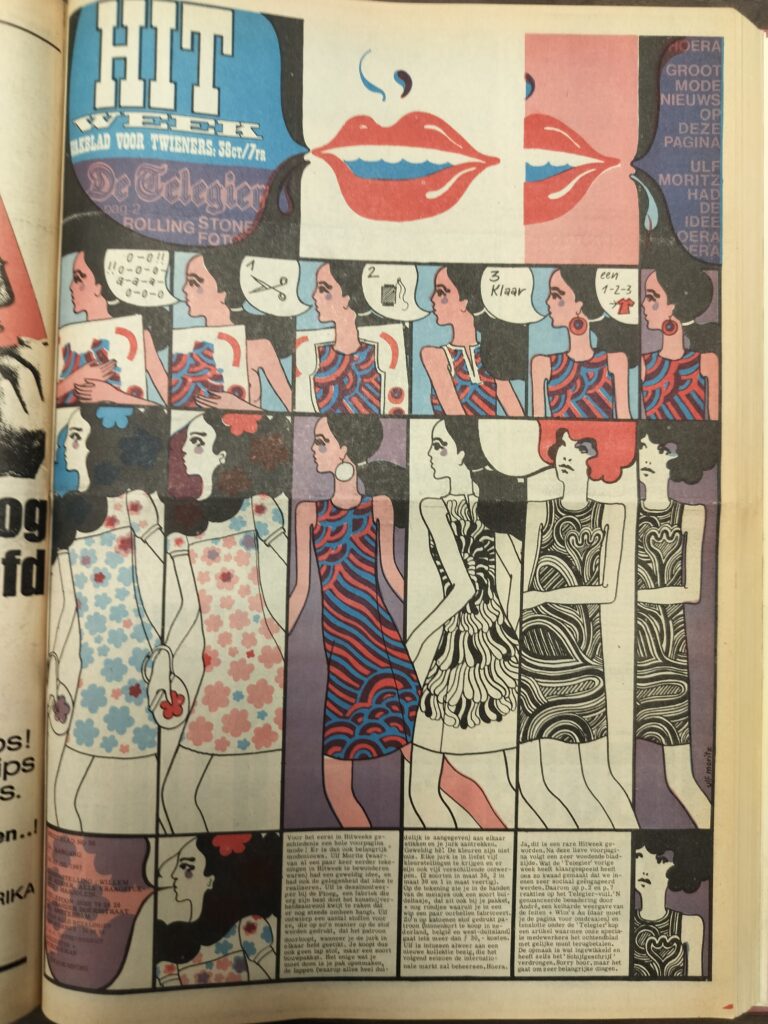

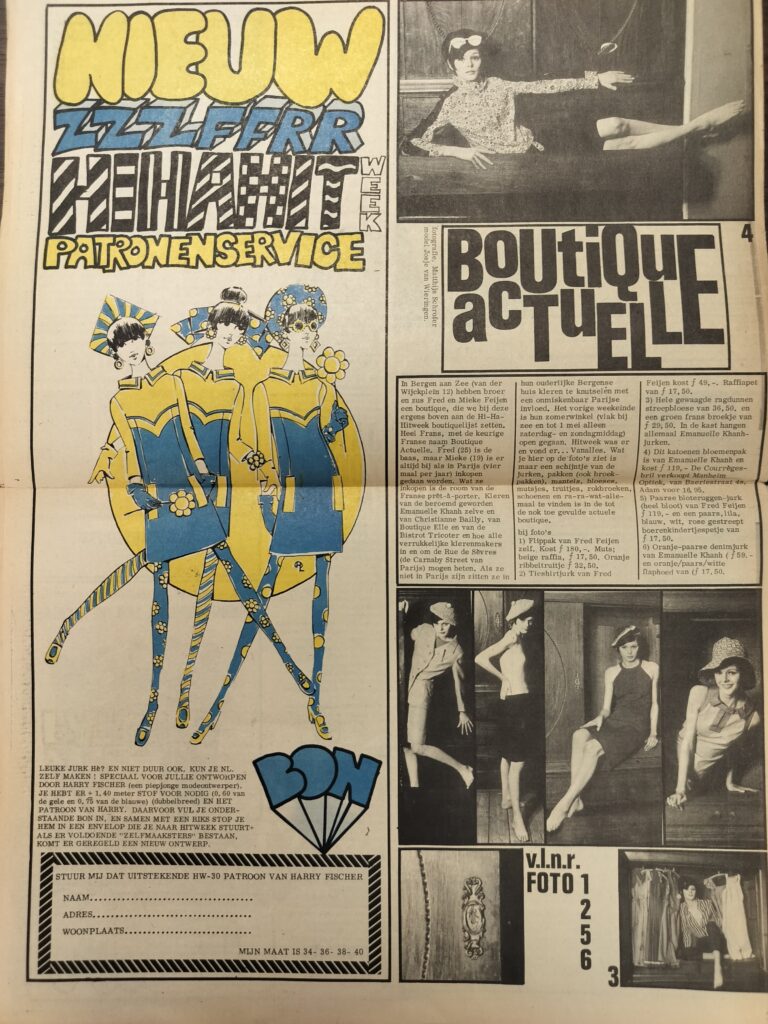

Like many people of my generation, I did pick up Hitweek from time to time during the years it was published. In later years, I mainly saw it in display cases in exhibitions or in books or in the media, and then it usually revolved around one and the same front page. But for my book, I had gone a step further and consulted Het beste uit Hitweek 1965-1969 (The best of Hitweek 1965-1969), compiled by Willem de Ridder and Frank Dam. After re-reading my blog, I became uneasy. Had I looked too much through Willem’s glasses? That’s fine of course with a source reference, but what if those glasses are too magical? Are you not depriving yourself and your reader of information and insights that may be just as interesting as what you show through his colourful glasses? Over the past month, I have gone through almost all the issues of five volumes, and my conclusion is that De Ridder and his fellow editors’ wishes were essentially the father of the idea, but that steps were always taken to get closer to that goal. Undoubtedly, many buyers felt that it was their magazine. With great tenacity, attempts were made not only to involve young people in the magazine, but also to lure them out of their shells. Through something as simple as a talent show focused on clothing design or by supplying cutting patterns, what is also a form of DIY. An interesting step was the introduction of the section ‘Hallo die dokter’/ ‘Dag dokter’ (hello doctor/goodbye doctor), which started in May 1968, and was intended as a post box for sensitive questions, a kind of cover for questions about sexuality too. The magazine targeted young readers, but there are several indications that it also had older ones.

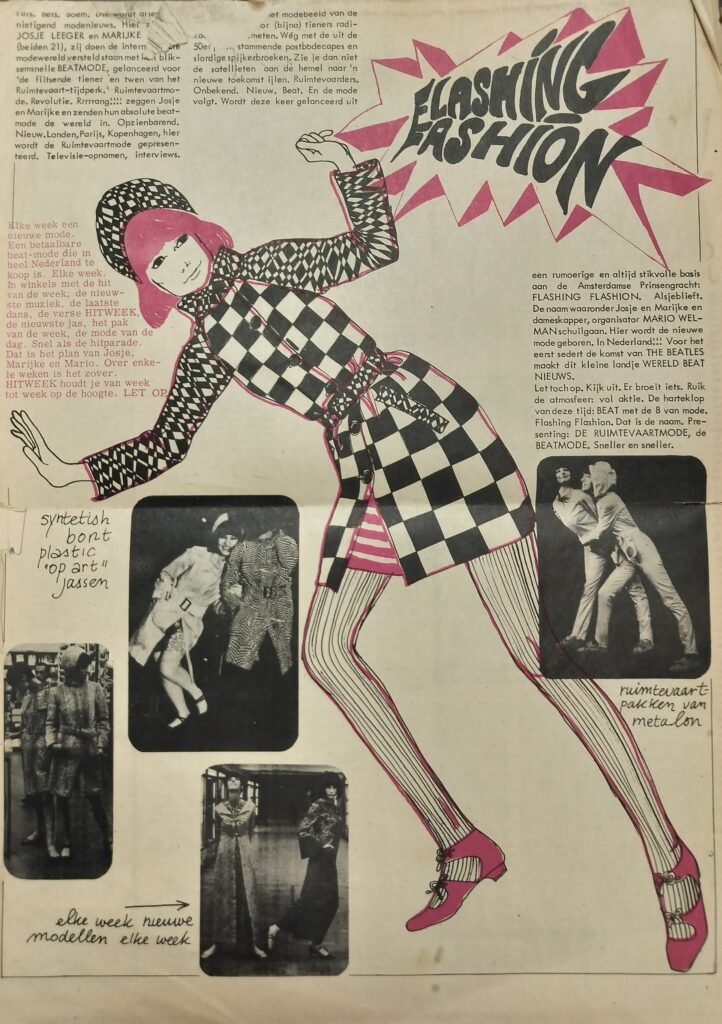

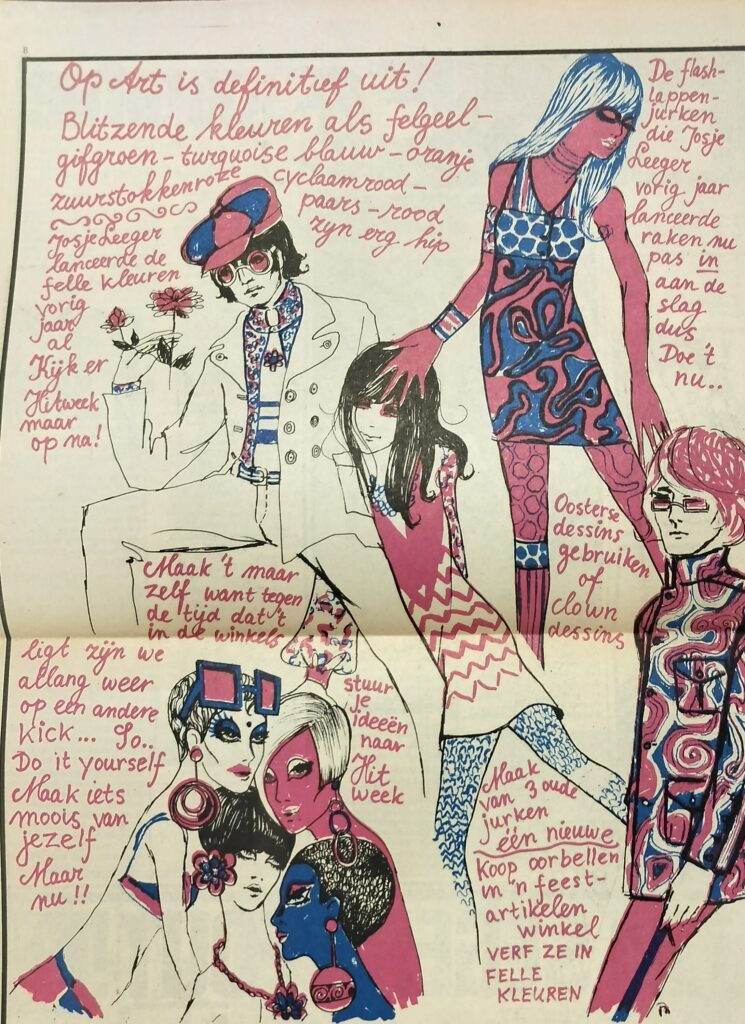

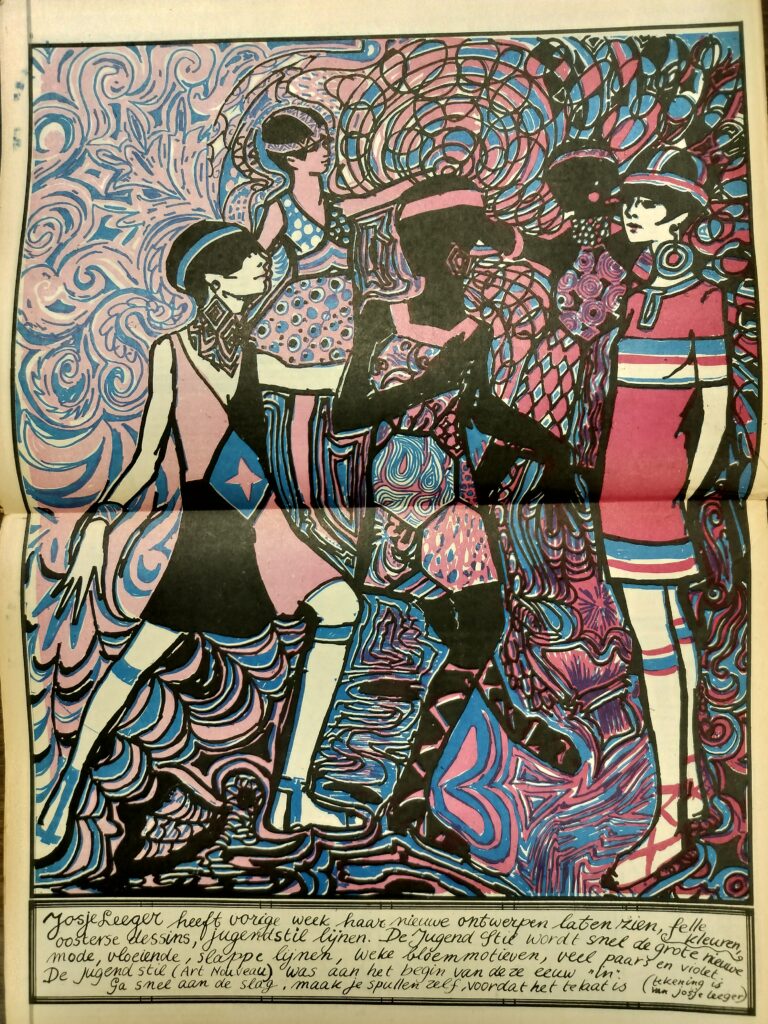

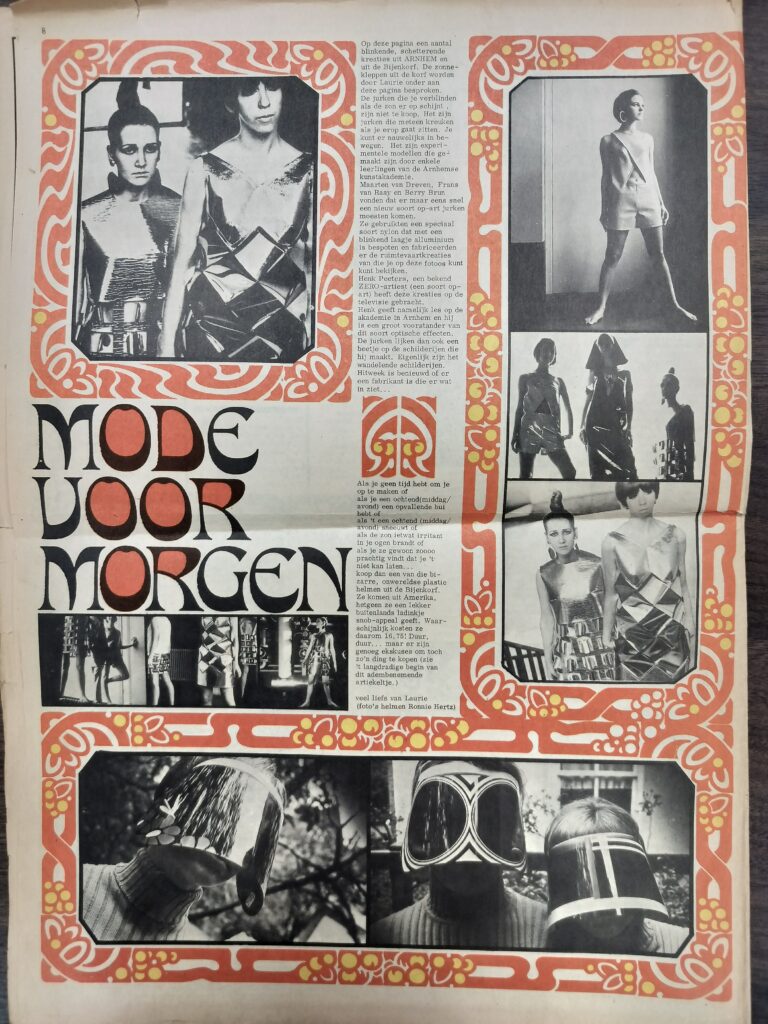

Every week, Hitweek published the charts, living up to its name, supplemented with music calendars and articles about pop musicians. Dutch artists featured remarkably often, with (Golden) Earrings, Wally Tax and the Outsiders, Cuby + Blizzards – mý band in those years -, consistently at numbers 1, 2 and 3. When it came to English pop music, Hitweek faithfully followed the most popular bands, but to the Netherlands, it clearly had its own favourites. However, there was so much more to Hitweek than that. If you wanted to know what the progressive cultural elite of the Netherlands was interested in and what the editors thought twieners should be aware of, you could find it in Hitweek. To list book reviews – I, Jan Cremer (1964) (English edition of 1965), sensational films, political events, personalities such as the poet Johnny the Selfkicker, television presenter Mies Bouwman, writer and journalist Renate Rubenstein and visual artist Yoko Ono, and last but not least, fashion – youth fashion! Between September 1965 and September 1967, we are successively alerted to art-related fashion, when it was ‘out’ and when for example more colour was coming into fashion.1 Still mostly abstract forms, floral motifs stood out, with Hitweek always making the link both with more or less contemporary visual art such as op-art and zero, but also older styles – De Stijl and Jugendstil [Jugend Stil], that became a true neo style, heralding a bigger leap in the autumn of 67 after the Summer of Love, when the sheepskin and fur-lined Afghan coat became the hippie’s dream.

In just over a week, it will be three years since De Ridder passed away. A good moment to give him the honour and attention he deserves. With his background in Fluxus, the performing arts and through his sensational Papieren Konstellaties (Paper Constellations), no one was better equipped than him to naturally incorporate all the above mentioned cultural phenomena, which defined the 1960s, into Hitweek. During his years at Hitweek, he developed into an increasingly serious graphic designer and organiser. He remained an man of ideas and ideals. As you can read in Hitweek the Netherlands was no rival to England when it came to pop music, but nothing similar was openly said about fashion, even though there was reason to do so. With the next stepping stone, the opening of Paradiso and Fantasio, of which De Ridder was one of the initiators, a dream came true, because these platforms as we can read in Hitweek made “Amsterdam the centre of the world”.

In the name of Amsterdam, thank you, Willem!

Designs by Jos Leeger. “Jugend Stil is quickly becoming the big fashion… Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) was ‘in’ at the beginning of the century: Get started quickly, make your own stuff, before it’s too late.”

One of the headlines mentions the first pop festival in the Netherlands, Hai in de Rai, which took place on 11 August and in which

Willem de Ridder had been closely involved.

- See more about Josje Leeger and Marijke Koger in the television programme Hoepla and their involvement in The Fool in my forthcoming book. ↩︎